The drama surrounding 20th Century Fox’s latest attempt at The Fantastic Four has been nothing short of insane. Beyond the vengeful tweets from director Josh Trank, the allegations of property damage during the production, Trank’s antisocial behavior, and his outward animosity toward Kate Mara on set, there are the expensive reshoots to patch together the last third of the film, Mara’s terrible reshoot wig, and the news that the actors were constantly directed by Trank to perform as flatly as possible, even being told when to blink and breathe (that’s not a joke).

As if that wasn’t enough, there’s another elephant in the room; one that a few articles have mentioned, but haven’t completely explored. The fact that 20th Century Fox approved Trank’s pitch for this re-launch of the franchise. I can’t imagine the pitch was too vague to be understood. Trank said right from the beginning that he envisioned a David Cronenberg-style “body horror” film. That’s pretty specific. There’s little room for misinterpretation.

I can only draw one conclusion from this evidence: The suits in charge at Fox don’t watch movies, they probably haven’t seen a Cronenberg film, they likely didn’t watch Trank’s "Chronicle," and they make decisions completely subjectively in the same way “good ol’ boy politics” is conducted. “I don’t need to understand his pitch because I like the guy, and that’s enough. I’ve got a good feeling about this guy.”

This is how catastrophes happen.

To Hollywood execs (with the marked exception of Marvel’s Kevin Feige), all “superheroes” are the same. If a director’s vision delivers a great Batman movie, then in their minds that same guy can deliver a great Superman movie (even though we who actually read comics know that’s just not true).

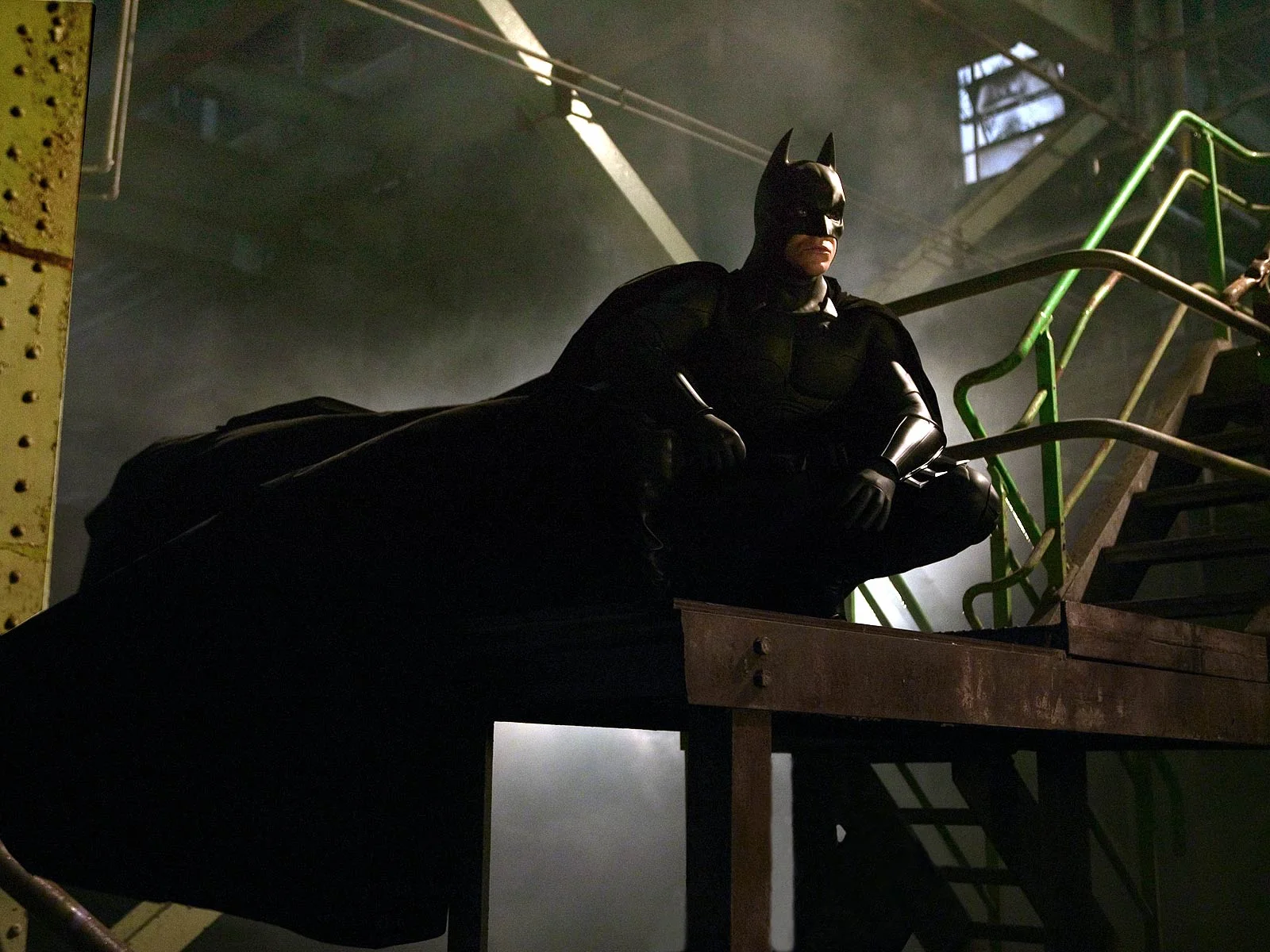

Hollywood has also been in a torrid, extended affair with “dark” for the past decade. If you don’t know who “dark” is, he showed up with 1999’s Matrix and officially entered comic book films as a publicized thing with Batman Begins. Now, if you were to ask me, 1989’s Batman film was plenty dark. The perfect amount of dark. Ask Hollywood, and they’ll call 1989’s Batman “cheesy.” “Dark” isn’t an objective descriptor anymore. It’s a damned genre all its own!

With Batman, “dark” remained well hidden, because Batman as a franchise can absorb a lot of “dark” without it being out of place. But when Sony rebooted Spider-Man as The Amazing Spider-Man, they publicized that more “dark” would be added to the formula. Warner Bros. vomited Man of Steel on audiences, the first Superman anything that children couldn’t go see, that was infused with so much “dark” it wasn’t even a coherent narrative experience, and that’s regardless of the fact that it was tonally dishonest to the Superman character.

In the background, Marvel Studios and Disney are making highly successful comic book films that only get about as dark as 1989’s Batman. Marvel Studios still uses dark as a descriptor for certain scenes and moments, not a cinematic formula to be spray-painted over an entire film (although their titling of Thor 2 as Thor: The Dark World was a bit irritating).

On the eve of getting a film in which Batman and Superman will hate each other in a monochromatic world, enter Trank and his trank wreck, er, train wreck of an idea for Fantastic Four. The rule of thumb is this: Yes, let’s invest hundreds of millions of dollars in films based on these 50- to 80-year-old characters because they are still immensely popular and will make us major bank. However, we’re really uncomfortable with everything they’re about; from the way they look and act, to the universes they inhabit. So let’s change all of that.

Hollywood doesn’t understand that there’s a connection between long-term popularity and familiarity. Change it so completely that it becomes a stranger and watch audiences reject it.

We’ve liked these superheroes for decades because they don’t change so radically that we don’t know them anymore. These fictional heroes are safe havens while our real worlds experience illness and loss, duress and death. I don’t know about you, but I enjoy superheroes because they allow me to escape to a positive place for a moment. A place of fantasy and hope. I don’t need superheroes to remind me how crappy everything can be or how full of angst and despair a person can become.

Trank’s Fantastic Four looks to be the first “dark” infused comic book film that’s collapsed under its own weight. The audience has spoken that this is too much “dark.” Could we be at the verge of a turning point?

This entire thought pattern led me backwards looking for an answer. Fantastic Four is in a unique position in which it has had four films in 21 years. Of those four films, the 1994 Roger Corman one has gone down in infamy, so “low-budget embarrassing” that Marvel paid them off not to release it, and now it can be seen on YouTube.

We all know the fate of the 2015 Trank version. So bad that Fox wishes they didn’t have to release it, but that $120 million price tag forces their hand.

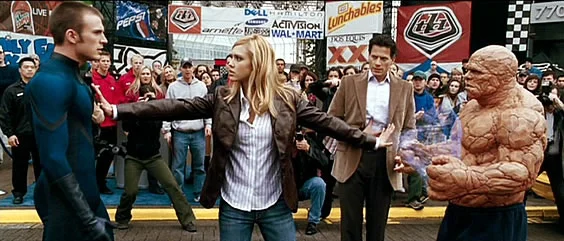

Then there’s the 2005 version starring Chris “Captain America” Evans and Jessica Alba, along with Michael Chiklis and Ioan Gruffudd. This is a film that made $330 million dollars at the box office and earned a sequel that made $290 million dollars.

I won’t try and claim the 2005 Fantastic Four was a work of genius, but I saw it in the theater, just the one time, and I don’t recall walking away with anger in my soul. Now, the sequel on the other hand made me grumpy. But let’s not worry about the sequel. We’re talking about cinematic adaptations of the origin and characterization of The Fantastic Four, so the 2005 version is our lost “middle child” between Corman and Trank.

Directed by Tim Story, the film is caught at the cusp of a seismic shift in comic book films. The Sam Raimi Spider-Man films, which walked a line between semi-serious and comic camp, were at the height of their box office power. In the background, the X-Men films were the sarcastic, moody cinematic sibling.

Enter Story’s Fantastic Four…the same summer as Batman Begins. The Nolan Dark Knight saga landed and succeeded in bringing “dark” to comic book movies. The more lighthearted, humorous Fantastic Four couldn’t stand alongside it with audiences. Why?

Having not seen it since 2005, I grabbed a copy and got to watching. The result? A mix of understanding and sheer relief.

Was it a perfect film? No, not by a long shot. As far as comic book films go, it has some disadvantages. It’s a very small story that lacks the scope and grandeur of a Silver Age Fantastic Four comic saga. The plot has a number of contrivances in the peripheral elements that lend to eye-rolling. Why exactly was Ben Grimm’s fiancé conveniently on the bridge after the big rescue scene? Things like that.

The criticisms about the costume for The Thing are warranted, given that he’s also way too small in stature compared to the comic book character. The production took a shortcut there by not using digital trickery to make him a bit more massive, but at least he’s not a lousy CGI video game character.

As far as special effects go, Story’s film has no breakout effects milestone. They range from serviceable to less-than-convincing. I imagine this was both a budget issue and a result of the film now being a decade old.

The origin story of Dr. Doom is a train wreck for comic book purists. Giving themselves less than two hours to establish both the origin of the Fantastic Four and Dr. Doom, they smashed them together and the result is polarizing.

What, you ask, could possibly be left over that’s any good? Well, what proved a mediocre viewing experience in 2005 is a badly-needed respite in 2015.

For one, the cinematography is brightly colored and fun. The heroes are humorous and Chris Evans’ Human Torch is quippy and exuberant. The performances are solid, Jessica Alba was at the height of her popularity at the time, and the story moves at a good clip. I was laughing with the movie and I’m ok with that. I was also thankful that it wasn’t “Whedon-style” dialogue. Frankly, I’m burnt out on Whedon and all of his imitators.

The writers didn’t avoid giving the characters their comic book names, something that’s become far too prevalent in modern comic book films where the writers are reticent to use the source material at all aside from the title. They also didn’t avoid giving them costumes, albeit costumes that came from the X-Men film philosophy of understating their comic book trappings.

But there were two major elements of the film that resulted in me forgiving the movie of some of its sins.

- The four struggle with their newfound abilities but ultimately embrace them and become heroes.

- These superheroes actually save people in peril and prevent death and destruction.

Looking at Story’s Fantastic Four through the dystopian lens of comic book films of the past decade – looking back through Man of Steel, Dark Knight Rises, the Spider-Man reboot, the spate of recent X-Men entries, and now Trank’s mess – the 2005 Fantastic Four is more of what I want from a comic book film than don’t want. And that’s key.

What sets Generation X apart from Millennials and Boomers has been our unquenchable appetite for our own nostalgia. We revere and embrace it like no other. However, I’m starting to believe that such a gift has come at a tragic price.

Previous generations were able to separate from their childhood interests and in doing so, preserve the purity of them so that Superman in a 1940s movie serial and the 1978 feature film were still in essence the same character that could be enjoyed by children and adults alike. The adults making the 1978 film were the kids that read the 1940s comics. Yet Superman remained the same.

Generation X has not separated appropriately from our childhood icons. Because of this, our generation has largely not reconciled our adult minds with our childhood interests. We want our interests at the age of 5 to grow with us into 35 and 45 and beyond. Gen X is trying to jam a square peg into a round hole psychologically, so instead of becoming adult stewards of these characters for future generations of children, we’ve instead dragged these characters and properties along with us as we’ve aged and attempted to transform them into adult-level entertainment with all of the jaded trappings that come with the adult mind.

The result is a disservice to those creations, to our memories, and to the children behind us who are growing up with fewer and fewer heroes because of “creators” like Trank, Zack Snyder, Mark Webb and others who are making superhero films that don’t respect our nostalgia, the source material, or allow the next generations to view them at those crucial young ages.

I fear Gen X has lost its objectivity while white-knuckling our memories. Instead of guarding these characters, we’ve decided we own them, to the disadvantage of everything else. Generation X has a lot to be proud of, but we also have a lot to think about in what we demand of these properties versus what they were always intended to be and do.